He Said, She Said

Dispelling the Myth of No Evidence

by Caroline McKuen

It was the very first meeting at which the Presbytery of New York & New England considered our case. It was a big case—five women bringing charges against a pastor in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church for colluding with abusers to harm women and children in his congregation.

At the meeting, another pastor - retired after serving in ministry for decades-stood up to speak about the charges.

“These women have no way of proving their case.” He waved his hand toward the women dismissively. “It’s he said/she said. None of us were there to see these alleged sexual assaults or abuse situations. Memories are faulty. Maybe these women think they know what happened and they are just imagining things. There is no point in looking into this. We mustn’t waste the time of the Presbytery considering what may be sheer slander and speculation.”

He bolstered his argument with allusions to Jezebel and Delilah, “evil women who bring down godly men.” And he cautioned against violating the ninth commandment.

This speech and others like it are met with applause in many circles of the OPC, in which can be standard practice to assume that abuse allegations are ethereal, unprovable, and based entirely on witness testimony.

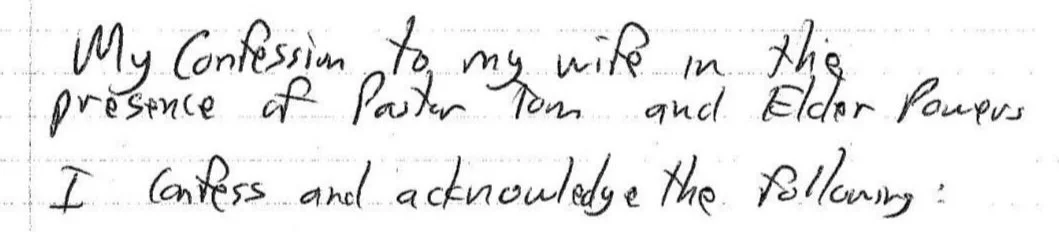

But the reality of our case was far different than the pastor had described in his speech. While there were multiple witnesses in the case (six female victims and also two pastors who had witnessed various aspects of ongoing abuse situations), the case did not rely on witness testimony. In fact, there were hundreds of pages of texts, emails, and letters, as well as several photos and audio recordings in evidence. The evidence had not yet been distributed to the entire Presbytery, but it had already been collected and catalogued by the women and handed over to the committee assigned to investigate. Furthermore, the documents entered as evidence were compelling. They included two confessions written by abusers, one in the presence of witnesses. Also included were church trial records, CPS reports, and letters and emails from the accused pastor to the women. We had also notified the Presbytery that we had more information available if they wished to see it—including medical records. The case was not “he said, she said” at all.

So why would a pastor immediately give a speech at Presbytery assuming a total lack of evidence before he even checked into it? I cannot speak with certainty about his personal motives, but there are several common reasons abuse is presented this way.First, abusers love to define abuse as a vague and mysterious matter. Abusers thrive on hazy ground. They do not feel they need to appear completely innocent. It is usually enough to muddy the water a bit. And water can be muddied any number of ways. Did Fred kick his wife in the face? Well, define ‘kick.’ Define ‘face.’ And do you know the intent of Fred’s heart? Perhaps Fred’s wife said something rude and she deserved to be kicked. Perhaps his wife was drunk and he was trying to sober her. Who knows why weeping women turn up in the emergency room with boot prints on their faces claiming to have been violently assaulted? It might be a hormone thing. Although this is clearly a fictional example, it is not far removed from reasoning I have heard many times around abuse cases. Abusers stir confusion whenever and wherever they can because it serves their purpose. They do not try to mount a coherent defense. They just throw random excuses at the wall, hoping something sticks. They give vague, self-contradictory accounts of events. They attack the character of the victim and witnesses. They claim to be scapegoats of society. They are not aiming to come out completely vindicated (which would be impossible). All they have to do is convince the bystanders that the situation is complicated. If the abuser succeeds, then the victim's supporters fade away and the victim stands alone. That is all the abuser needs to keep abusing.Secondly, bystanders are often all too eager to accept abusers’ chaotic version of the nature of abuse without examining the evidence. If a pastor acknowledges that abuse is happening, then he will be obligated to act on that. He will have to offer assistance to the victim. He may have to stand up to the abuser. He may have to question his own judgment about some of his friends and fellow pastors. He may have to call the police. All of those things are uncomfortable, time-consuming, and risky. It is much easier to adopt an attitude that “these things cannot be proven,” without ever actually bothering to look into it. Particularly in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, refusing to hear evidence is often celebrated as noble, an effort to "preserve the good name" of accused man—which is all the abuser needs to keep abusing.Finally, some pastors who are “bystanders” are also abusers. Although we hope this is not a common reason for pastors to adopt such an attitude of disinterest in abuse cases, we must acknowledge that this also happens. If a pastor has done abusive things to members of his own congregation, he is not likely to want to put another man on trial for the same behavior. He cannot defend abuse in public, of course, so he may adopt the usual “who can really know?” tactic that leads to an easy dismissal.Having worked in domestic violence advocacy for some years now, I can say with certainty that abuse is usually remarkably easy to prove if someone wants to know the truth. Abusers tend to have a strong sense of entitlement and superiority, which leads to carelessness with evidence. They assume they will be able to talk their way out of any negative consequences, and sadly, they are often correct in that assumption—which leads to further carelessness with evidence. The more they get away with abuse, the less they worry about anyone knowing about it. And the evidence just keeps piling up.I have worked on an abuse case in which a woman had strangulation bruises and a broken wrist. The police literally arrive to find her abuser standing over her holding a baseball bat. But her abuser still tried to claim her case was unprovable because she “could have gotten those injuries anywhere.” I have worked on a case that was recorded by the woman from a cellphone in her pocket documenting threats to shoot her. The abuser still tried to claim the recording wasn’t “real evidence” because he didn’t plan to shoot her, just to scare her. “It’s classic ‘he said/she said’,” they both claimed. With so much obfuscation about abuse, it is perhaps unsurprising that a pastor in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church would begin an investigation by assuming (without even looking into it) that accusers have no evidence—that it is all “he said, she said.” But it is still disappointing. Those who have sworn to care for the flock should have a true interest in their welfare. Pre-judging a case before even opening an evidence file, or in some cases refusing to even look at evidence--these are not noble actions for overseers charged with the care of vulnerable people. “He said, she said” is largely a myth perpetuated by people who (for whatever personal reasons they may have) do not want to know whether abuse is happening. For those who do want to know, the evidence is usually abundant and overwhelming. In our case, the evidence included eight witnesses, hundreds of documents including two abuser confessions, and several photos and recordings. The problem wasn’t at any point a lack of evidence provided by the women. But no amount of evidence will convince someone who doesn’t want to know.(Image at the top of the page is the first line of a confession letter hand-written by one of the abusers in our case, witnessed by two members of the Session.)